We Have Been Here Before: Black Folk and the American Presidency

I went to bed last night in America and woke up this morning in America. This is America.

Nikole Hannah-Jones

~ Did America just elect someone who is a convicted felon as the 47th president of the United States of America?

~ This cannot be real!

~ How did we get here?

These are just a few of the text messages I received on Wednesday, November 6, 2024—less than twenty-four hours after Donald Trump won a decisive victory in the 2024 presidential election. I watched the returns early Tuesday evening, then decided to take a melatonin tablet and head to bed around 9:30 p.m. To me, this election felt strikingly similar to those in 2004 and 2016. The Democratic presidential candidate’s messaging once again appeared unorganized and disconnected from what the people were currently experiencing. And as with Bush in ’04 and Trump in ’16, the Republican candidate’s message, was laser-focused on promises to improve the lives of the common man and woman. In 2024, millions of Americans decided yet again that extreme conservativism is who we are at our core, at least for now.

My grieving over this election only lasted a day or so. Though hopeful, I was skeptical that VP Harris or any Democratic candidate would win this election. The historian in me would not allow myself to fully believe that America was truly prepared to move beyond what the novelist James Baldwin referred to as “the lie”—the lie of black inhumanity, the lie of black inferiority, the lie that black folk lacked culture, and the lie that black folk lacked a true home.

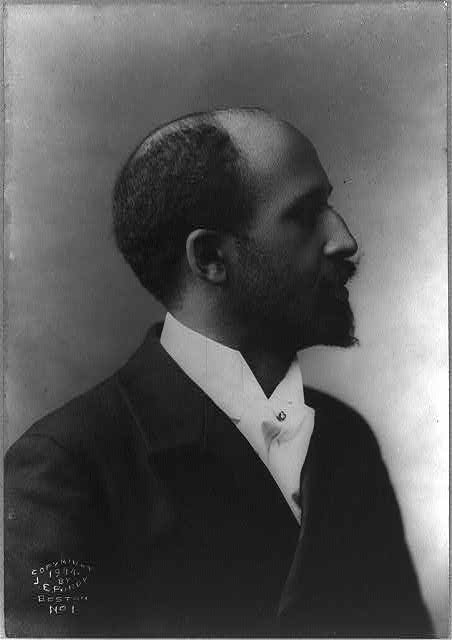

This lie has, in many ways, hindered this nation from becoming a true democracy. Like many of my historic mentors in their youth, Baldwin, W. E. B. Du Bois, Frederick Douglas, and Martin Luther King, Jr., I continue to strive hard not to become pessimistic about the “American dream.” However, moments like this most recent presidential election make it hard not to lose faith in this “great experiment.”

How did we get here, and how might we work through this moment? Historically, when these episodes of political disappointment occurred for the black community, they reassessed the outcome, strategized to glean a path forward to secure rights, and organized around their common causes.

For example, when black folk were systematically disenfranchised with the implementation of the Mississippi Plan of 1890, the black community shortly got to work to counter the impact of those adverse laws. They began to focus on ensuring that black folk had access to proper education via the creations of hundreds of black colleges from the late 1890s to early 1900s for the sole purpose of creating an educated voting mass. While the fight to restore broad enfranchisement took nearly seventy years, black folk never stopped struggling to secure these rights—with an eye on gaining full access to the American experience.

Yes, America, we have been here before! Since the first election of Abraham Lincoln, black folk have endured the emotional roller coaster of presidential elections. In 1860, one of the major platforms of the Grand Ole Party spoke vehemently against the institution of slavery in the United States. When Abraham Lincoln won the election, there was a deep sense of hope that spread throughout the black community: a hope that soon, the country would no longer see them and their ancestors as personal private property, but as citizens of a country that they built with their forced labor.

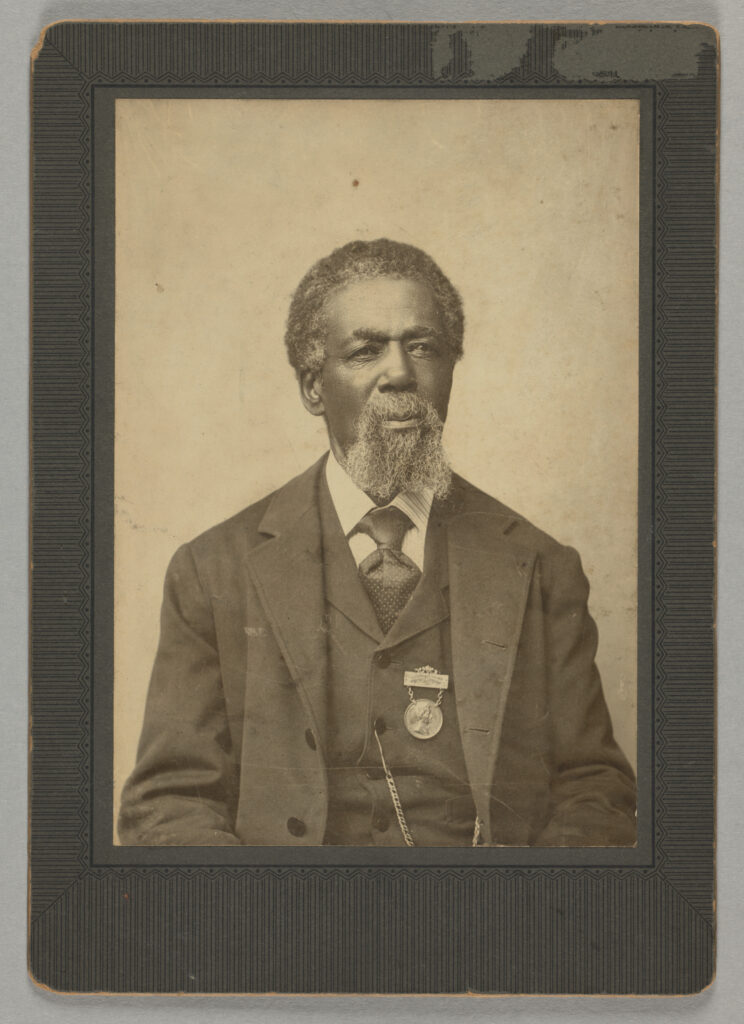

Lincoln’s election, as we all recall, did not lead to the quick abolishment of slavery but to a civil war, still the deadliest, bloodiest war in this nation’s history—a war that lasted four years and bled into Lincoln’s second term. This was a war that was ultimately won by Union soldiers, Lincoln’s political maneuvering, and hundreds of thousands of black men and women—free and enslaved, risking their lives and liberty to secure the freedom of their brothers and sisters who were still in bondage.

The euphoria of learning they earned their freedom was short-lived, as Lincoln was assassinated shortly after Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Virginia. The hope of Lincoln’s presidency ended not only with his demise but with his successor’s eagerness to accept members of the Confederate States of America back into public office in the US.

Reconstructing the nation that was established with the institution of slavery at its root was made more difficult because President Andrew Johnson, a Southern sympathizer, moved to bring the nation back together—but without regard for black folks’ rights. Nonetheless, many Americans insisted, for the first time in American history, that black folk be included in the US Constitution.

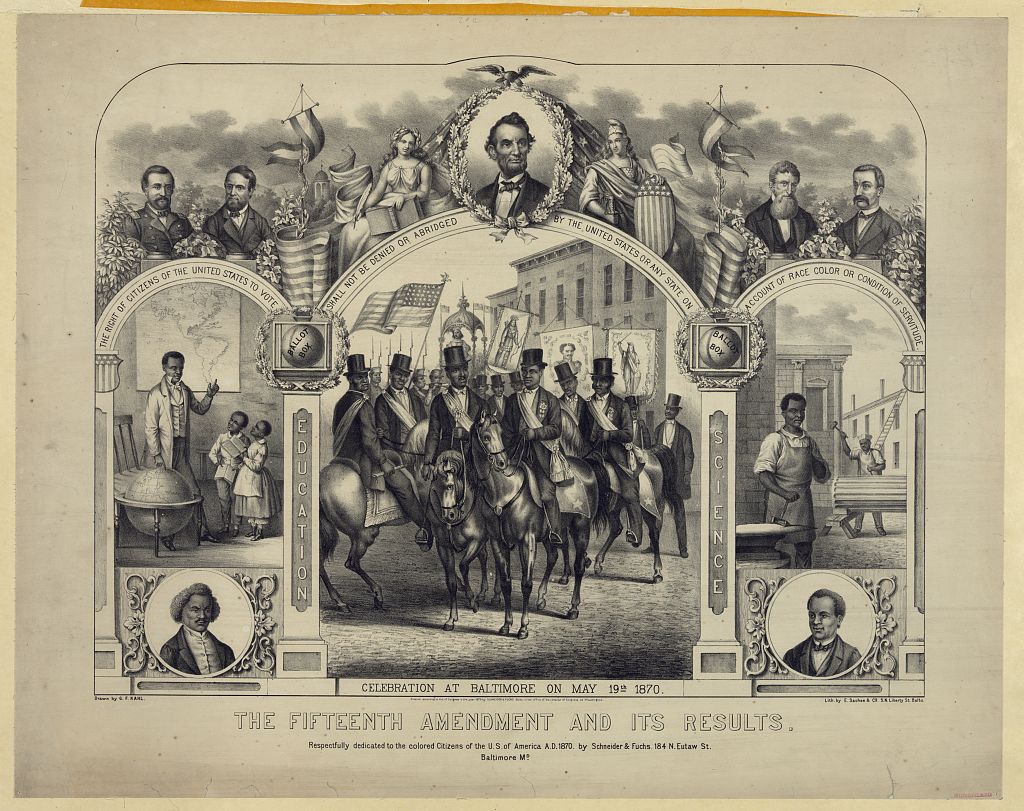

Between 1865 and 1869, Congress passed three landmark amendments: the 13th abolished slavery, the 14th granted federal and state citizenship to everyone born in the United States, and the 15th granted the right to vote to all male citizens.

These gains were met with immediate white backlash in 1866 with the creation of the Knights of the White Camelia in Pulaski, Tennessee. This militant, Christian terrorist organization (a precursor to the Ku Klux Klan that reemerged in the early twentieth century) was established to “take the country back” to a time that resembled America before the end of slavery. For nearly twelve years, black leaders and their allies attempted to integrate black folk into the political and economic fabric of the United States, while white supremacists politically and physically fought to ensure they were excluded.

Still, even though only a small number were eligible, black men voted for the first time in the presidential election of 1877. It was the first election in which black folk participated—but was also the first instance they had their political hopes dashed at the ballot box.

A close vote led to the Compromise of 1877, which awarded Rutherford B. Hayes the presidency and allowed the Southern states to govern themselves, thus abandoning black folk for more than a generation. Without federal oversight (and the presence of US troops) to ensure that black folks’ newfound rights were secured, Southern legislators systematically passed new laws that grossly limited black folks’ ability to vote and serve on juries, thus creating a new political norm in the nation’s history.

Similar to the current state of politics—anytime the marginalized in society made gains toward inclusion in the American experiment, a massive blowback has followed. Specifically, Reconstruction was replaced with a generation of Jim Crow Laws; and the Second Reconstruction or the Modern Civil Rights Movement was followed by an era of Neoconservative policies emboldened by Ronald Reagan’s presidency. Now, perhaps what we are experiencing is the backlash to an Obama presidency that was more symbolic than policy-driven, however impactful.

Time and again, black folk have gone to the polls, delivering their votes for both the Republican and Democratic candidates for president for over 150 years. Presidents like Theodore Roosevelt pandered to the black community when in 1901 he invited Booker T. Washington to the White House for dinner. The image of a black man having dinner in the White House angered white Southerners so much that Roosevelt conceded the Southern vote to the Democratic party in his following election. In some ways, this backlash is similar to the backlash that the modern Democratic Party faced in elections since Obama’s presidency.

Although Washington served as an unofficial advisor to Roosevelt, the sting of segregation and racial violence in the South still poisoned American life under the Roosevelt administration. Taking one term off from the presidency, Roosevelt decided to run for the presidency again in 1912, this time running on the Bull Moose Party ticket—a progressive ticket that spoke in some ways for social justice and providing women a minimum wage. When the presidential votes were counted, Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic nominee from New Jersey, won the election—with the support and endorsement of W. E. B. Du Bois’s editorial in The Crisis magazine.

In some ways, Du Bois’s endorsement of Wilson resembles members of the black, Hispanic and other marginalized communities who supported Trump’s candidacy in 2024. Specifically, Du Bois was rightfully concerned with Roosevelt’s lack of movement on black folk’s human rights during his first term as president, and therefore, decided to try the next option. Similarly, the small, yet significant percentage of black and brown folk who voted for Trump (or did not vote at all) were displeased with the Biden’s administration stance on several issues that adversely impacted their communities. Thus, they either voted to give Trump a chance or didn’t vote to ensure that neither Biden nor any member of his cabinet won the presidency.

If these frustrated voters, had considered the outcome of Du Bois’s endorsement, perhaps their support for Trump in 2024 would not have materialized. In September 1913, Du Bois penned an open letter to Wilson in which the noted historian and sociologist pressed the president on his plans for the 10,000,000 black folks in America. Du Bois reminded the president that just before this election, The Crisis endorsed his presidency as a lesser of the two evils—an endorsement he hoped he would not have to apologize to the black community for due to Wilson’s lack of commitment to secure their rights.

Specifically, Du Bois called for the end of lynchings, the end of Jim Crowism, and the end of the public humiliation associated with segregation. Wilson’s response never came. However, his actions were clear.

Just two years later, the president hosted a public screening of D. W. Griffith’s film Birth of a Nation (1915) in the White House, favorably comparing it to “history written with lighting.” Similarly, for the folk who believed they could not vote for Harris due to their frustration with the Biden administration, the first eight days of the new Trump administration delivered executive orders that specifically attacked the 14th Amendment and the Civil Rights Act. Like Du Bois, many of these voters are vocally expressing concern over their support for this administration. Indeed, we have been here before.

As a member of Generation X, I recall vaguely the Reagan years, but now as an historian, I understand how impactful they were to the current political landscape of America. His victory in 1980 marked the bginning of a conservative movement that targeted programs that adversely impacted government programs that benefitted not only black folk but also working-class people broadly. Reagan ended free lunch programs, cut public housing, and called for the elimination of the United States Department of Education—arguing that each state should control local educational outcomes.

Reagan’s political philosophy was the rule of the day; and for twenty-eight years, including under Bill Clinton, the nation has espoused a conservative political ideology supporting a “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” ideology. Similarly, President Trump’s most recent Executive Order to halt federal grants and loans harken back to Reagan’s fiscal philosophy. We have been here before!

So, how did we—Gen. Xers, Millennials, and Gen. Zers—get here? For the first time in my life—and my parents and grandparents’ lives, with the presidential election of Barack H. Obama, the first black President, black folk believed that change would come to America. However, shortly after his election, similarly to the Reconstruction era, the Tea Party was established in 2010 to “take their country back.”

Although Obama was able to have his signature legislation on healthcare passed into law, his presidency, in many ways, galvanized the people who created the MAGA movement in America today. It wasn’t the policies that the Tea Party and MAGA hated about the Obama presidency. It was the modern-day image of a black man in the White House that they hated, driving many of them to consistently vote against their own economic and health interests.

Donald Trump became the face of the MAGA movement during Obama’s second term by demanding to see his birth records and arguing that the president was not an American citizen. This, for me, harkened back to the idea that black folk were not citizens of the United States, and thus, the 14th Amendment, in the minds of MAGA supporters, was null and void. Despite—or because of—his overtly racist rhetoric targeting the nation’s first black president, US citizens, and immigrants from black and brown nations, Trump won a decisive victory in the 2016 election over Hillary Clinton.

For the most part, the majority of Americans—except those belonging to marginalized communities—appeared pleased with his presidency until he grossly mishandled the Covid-19 pandemic, which led to millions of Americans losing their lives—coupled with his mishandling of the racial unrest of the summer of 2020. I firmly believe that absent Covid-19 and Trump’s response to the the horrific death of George Floyd and subsequent protests, he would have won re-election in 2020. Americans, however, saw his leadership, or lack thereof, as too much of a threat to their lives to give him four additional years, especially during a global pandemic.

The 45th president lost the popular vote by more than 10 million votes and the Electoral College by 75 votes. Still, Trump and his supporters issued a call to “Stop the Steal.” Trump, the master salesman, brander, and showman, convinced a significant subset of Americans that the election results were not a representation of the true will of the people and, thus, the election was “stolen” from the people who voted for him. This concept, at its core, is anti-Democratic. Just as anti-Democratic as the Mississippi Plan of 1890 was—just as anti-Democratic as the Jim Crow Laws were and yes, just as anti-Democratic as many of the policies that were birthed during the Reagan era. Yes, we have been here before!

Despite the Democratic party solely campaigning on the tenets of “saving democracy,” the people chose to give Trump yet another chance. On Tuesday, November 6, 2024, nearly four years removed from January 6, 2021, Americans voted to return Trump to the White House. For the first time in almost a generation, a Republican candidate won the popular vote by nearly three million votes and secured the Electoral College by an 86-vote margin, delivering the now 47th president what he and his supporters consider a clear mandate.

So, where do we go from here, and how can we lean on the past? Folk who believe in this republic, must remember that this nation became what it is via the people pushing it to became what they desired it to be. The concept of freedom was imbedded at the very core of the idea of America. Freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of expression—we must make sure that in the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., that Freedom still Rings. Clearly stated, the collective must ensure that folk still have the right to organize, protest and push this nation toward a more perfect union, regardless of who holds the office of the presidency.

So today, how do we secure those very freedoms for the next generation? By ensuring that the 14th Amendment maintains birth right citizenship for all and not some. We must remember the work of Frederick Douglas and other black abolitionists who partnered with white politicians and white abolitionists to draft this amendment.

This took not one subsection of the nation but a broad coalition of its future citizens who pushed and organized to ensure that one day constitutionally black folk would become “whole” citizens. Likewise, we all must organize, strategize, and push to ensure that the 14th amendment and other liberties that are being attacked are secured. We do not have to reinvent the wheel — we have been here before!

Finally, with an in-depth study of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments we can learn how these leaders birthed coalitions and maneuvered the political process to secure their passage. With that, I am firmly confident that the rights of all “The People,” including the marginalized, can be secured for generations. This is why history matters—why the humanities matter—and why political science matters. Without the study of these fields and others, we as Americans will not understand the importance of E Pluribus Unum, “out of many one.” Indeed, we are many folks in this nation, representing many backgrounds. The vast differences, including cultural differences, are what makes America great. Yes, we can get through this period, but it will take us all—because E Pluribus Unum!

Reginald K. Ellis, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of History and African American Studies at Florida A&M University.