The Rise and Fall of Nagorno-Karabakh

On January 1, 2024, the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh ceased to exist. In less than two weeks, an Azerbaijani military offensive forced 100,000 Armenians to flee their ancestral home. The erasure of Armenians from this territory took place in full view of a global public--but Armenians were left on their own.

The Soviets established the republic in 1923 to manage the complicated demographics of the South Caucasus. The Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh (from “Mountainous Karabakh” in Russian but known as “Artsakh” in Armenian) was meant to afford the majority Armenian population of the region political autonomy within the new Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, leaders of Nagorno-Karabakh declared their independence from Azerbaijan—but Azerbaijani elites refused to give up claims on the enclave. In January of this year, this stalemate, frequently punctuated by violence between Azerbaijanis and Armenians, finally came to a violent end with a brutal act of ethnic cleansing that has not received the global attention that it deserves.

A recent video circulating on social media shows the Azerbaijani demolition of the Karabakh Parliament building on Renaissance Square in the former republic’s now depopulated capital Stepanakert. The symbolism of this act is particularly significant because on February 20 Armenians had traditionally celebrated the anniversary of a movement that began there in 1988. As changes swept across the late USSR, the Council of People’s Deputies of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region had requested the transfer of the territory from the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic to the Armenian Soviet Republic. Rallies supporting the unification of Karabakh with Armenia followed in the Armenian capital, Yerevan.

Shortly after, the protests took a violent turn. Nationalist activists expelled Armenians from Azerbaijan, and Azerbaijanis from Armenia. These expulsions triggered a new level of ethnic hatred that would later make coexistence nearly impossible. Between 1988 and 1991, anti-Armenian pogroms forced over four hundred thousand Armenians from Azerbaijan’s capital Baku, the industrial city of Sumgayit, and other places across Azerbaijan. In turn, Armenians violently displaced roughly the same number of Azerbaijanis living in Armenia. The conflict turned into a full-scale war. Armenia emerged victorious and took control not only over Karabakh, but also of seven surrounding regions of Azerbaijan with the aim of bargaining for recognition of the disputed Karabakh.

Twenty-six years and one month after the start of the Karabakh or “Miatsum” (unification) movement, Armenians from Karabakh gathered in Yerevan to commemorate the achievement of de facto independence for the Armenians of Karabakh for some three decades. The celebrations were mixed with mourning for the loss of lives and homeland during the conflict. However, this development worsened ethnic tensions between Armenians and Azerbaijanis and shaped the national identities of both nations following the fall of the Soviet Union. While Armenians celebrated their triumph, it shaped their national identity around notions of resilience. Conversely, for Azerbaijanis, the loss of Karabakh became a driving force behind their aspirations to reclaim the land and national pride.

The beginning of the end

Armenia and Azerbaijan faced a three-decade “frozen conflict,” with the occasional eruption of violence and constant fear of escalation. During three decades of “no peace, no war,” while Armenia was busy building the myth of the “strongest army in the region,” Azerbaijan increased its military and economic capacities and improved ties with great powers, preparing for war understanding that it will not face any serious consequences.

After coming to power in 2018, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan claimed that he would start the peace process from scratch, and was accused by the Armenian opposition of abandoning the achievements of the negotiation process. Pashinyan’s statements in Shushi in 2019 and after the July 2020 clashes further emboldened Azerbaijan’s aggression while prompting criticism from Armenian opponents at home. All of this contributed to what Pashinyan called an inevitable war in the region, diminishing the sovereignty of Armenia and leaving its position in the region devastated.

The final escalation took place in 2020, when hostilities marked the beginning of the gradual erasure of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenian presence. In September 2020, with Turkish and Israeli support and armed with advanced weaponry, Azerbaijan initiated a full-scale military offensive. Armenian forces of Karabakh managed to resist for six weeks aided by the Armenian army resisting six-week. On November 9, Russian peacekeepers brokered a ceasefire. Azerbaijan regained control over territories adjacent to Nagorno-Karabakh, as well as parts of the territories of the contested territory itself.

The Lachin Corridor, a vital link between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, came under Russian control; some 2,000 peacekeepers were sent to the region to oversee the fragile peace and ceasefire regime. Having the most power in the region, however, Russia failed to prevent the small clashes and escalations in Nagorno-Karabakh, gradually losing trust in the eyes of Armenian and Karabakh authorities, and, most importantly, the general public.

The end—Karabakh without Armenians

Following the 2020 war, Nagorno-Karabakh enjoyed a short period of around two years of relative peace. However in late 2022, following local fighting and Azerbaijani diplomatic pressure on Armenia to give up its support for the region, Azerbaijan moved to block the Lachin Corridor. This move created a humanitarian crisis in Nagorno-Karabakh. Given the inaction of Russian peacekeepers on the scene, it is clear that the Kremlin gave Azerbaijan the green light to initiate this blockade.

Deprived of food and medical supplies, the region was brought close to a humanitarian catastrophe. The culmination of the almost nine-month long siege was a new military operation by Azerbaijan aimed at taking full military control over the region. The fighting lasted around 24 hours, ending with the surrender of the Karabakh army and authorities. The blockade was lifted—but only in one direction for the Armenian population of Karabakh to leave for Armenia.

In September 2023, Azerbaijan launched another military operation, gaining control of the disputed territories that ended with a two-week mass exodus of over 100,000 Armenians. And on January 1, Nagorno-Karabakh Republic ceased to exist, as decreed by its last leader, Samvel Shahramanyan. Azerbaijani authorities arrested several former and current officials from Karabakh’s leadership. They now face prosecution in Baku.

Karabakh’s armed forces surrendered their weapons to Russian peacekeepers, who now monitor the empty buildings and cultural heritage of Nagorno-Karabakh. While Russia seeks to extend its presence there, Azerbaijani officials have announced on several occasions that the Russian peacekeepers will be asked to leave in 2025, when their mandate ends.

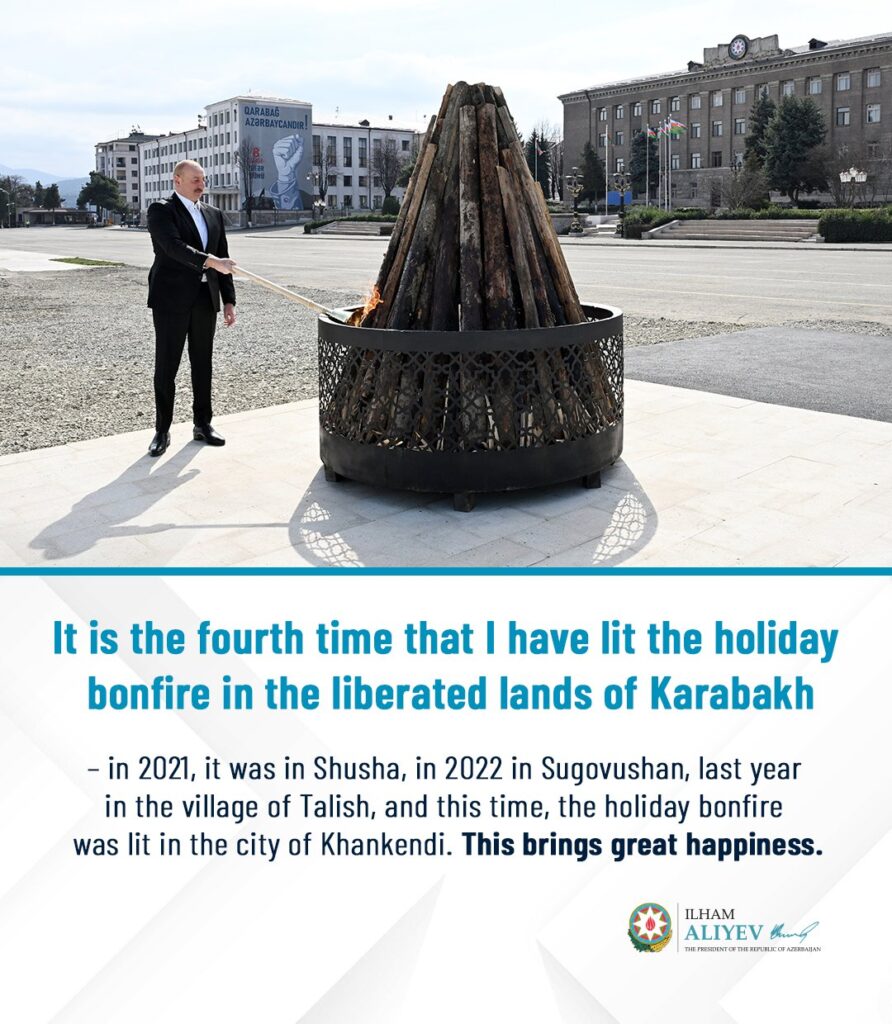

Meanwhile, having seized control of all of Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev adopted a new way of projecting power. He launched his presidential (re)election from the region’s capital, Stepanakert. Later, celebrating Nowruz (New Year) in the ghost town, Aliyev made reference to the “final cleansing” of the Nowruz bonfire, boasting of the ethnic cleansing of Karabakh of its Armenian population.

Meanwhile, Karabakh Armenian refugees, attempting to integrate into Armenian society, have faced unexpected bureaucratic obstacles regarding their refugee status and citizenship. Some are seeking refuge in Europe, where the war and its shadows are distant. Although various international actors periodically mention Karabakh Armenians’ right of return, neither the Armenian authorities nor the refugees themselves have high hopes about the chances of returning home, at least in the foreseeable future.

Armenia’s feeling of abandonment and the search for new allies

During the 2020 war, and again in September 2023, Armenia faced a stark reality: its hopes for support, particularly from Russia, were not realized. Although Armenians never had high expectations of the West, its indifference towards the region did not cause the Armenian public to switch sides as easily as Georgians and Ukrainians once did. In the end, Armenians felt abandoned and left to fend for themselves against hostile neighbors and an ally that was more of a coloniser to Armenia.

On the one hand, Russia brokered a ceasefire, ending a war whose continuation could have been even more devastating for Armenia and the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh. On the other hand, the myths surrounding the traditional Armenian-Russian alliance have collapsed, and the country is looking to the West for new, and hopefully reliable, allies to face future challenges that seem as dangerous to Armenia as the wars over Nagorno-Karabakh.

Western support for Armenia and the attention to the region was limited to geopolitical interests and power games. The mainstream Western media, too, did not pay attention to the conflict enough, covering it only during eruptions of violence, often serving as a textbook example of lazy journalism lacking basic fact-checking and context. The western coverage of the conflict intentionally or unintentionally created a limited understanding of the complexity of the conflict, oversimplifying it, trying to artificially balance the narratives or presenting the propaganda of one side only.

The choice of words and terms by media and politicians during the conflict did not prove helpful either. Some have mischaracterized the forced displacement of the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh as a “voluntary relocation,” ignoring the facts that make this a textbook case of ethnic cleansing. The mass exodus of Karabakh Armenians brought several top officials to Armenia, including the head of USAID, Samantha Power, and paved the way for further exposure of the hypocrisy of Western diplomacy towards the region. The statements of the U.S. and the EU about not tolerating ethnic cleansing in Nagorno-Karabakh were replaced by promises to protect Armenia’s territorial integrity after the completion of the expulsion.

What’s next?

The fall of Nagorno-Karabakh also highlighted geopolitical shifts. Russia, once dominant, found itself sidelined by Western mediation efforts, while Armenia looked to the West in vain to make peace with Azerbaijan, fearing another war that could destroy its sovereignty.

The resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict on Baku’s terms and Russia’s inaction throughout the process, as well as its apparent support for Azerbaijan’s offensive last September, seemed to be a turning point for Armenia to reconsider its asymmetric alliance with Russia. This has left the country more anti-Russian than ever.

This phase in Armenia-Azerbaijan relations is an opportunity for the two countries, their neighbors and the West, to step in and try to support stability and peace in the region. Along with the U.S. and the EU, Iran, neighbor to both Armenia and Azerbaijan, has become more interested in the conflict. Tehran has supported the two countries’ territorial integrity. And Iran has backed Armenian opposition to the so-called “Zangezor corridor” project–an Azerbajiani plan for a transport corridor across Armenian territory along its border with Iran to link Azerbaijan and the Azerbaijani exclave of Nakhchivan and Turkey. However, Armenia’s apparent shift of foreign policy and closer relations with the West are not appealing to Iran.

Azerbaijan’s military offensive in September 2023 marked the end of Nagorno-Karabakh’s existence as a political entity and the beginning of another generation’s trauma, further undermining trust in any authority, whether based in Yerevan or Stepanakert. The resolution of the broader Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict remains elusive, leaving a legacy of displacement, geopolitical recalibration, and unresolved ethnic tensions in the South Caucasus. And while the “resolution” of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was seen by some as a way to peace and maybe the possibility of coexistence of Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the peace talks seem to be as superficial as always, and tensions between the two nations remain as pronounced as ever.

Ani Avetisyan is a journalist who has covered Armenia and the South Caucasus region for over five years with a particular focus on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Aside from covering politics, Ani works on open-source investigations and fact-checking.