There’s Something in the Walls

How can our urban spaces shape public narratives of political and cultural legitimacy?

Have you ever looked around your town or city and considered why the main statues and civic buildings that surround you are there in the first place? Why those buildings? Why those people?

This is worth reflecting on because this architecture, whether commemorating presidents, Popes, or patriots, represents a declaration of who we are as a community, and where we’ve come from. Our civic buildings encapsulate a supposedly agreed narrative about who our most illustrious forbears were, and why they were important.

The point is that who gets to be on the pedestal and remembered is a highly political signifier of legitimacy and cultural value, while other contributions are left to ebb away into the collective unconscious over time. We might not think too deeply about all that when we are running down the street to catch the bus—but the space that surrounds us is indelibly connected to narratives of historical, political and cultural legitimacy. Many of these are of course greatly valued, inherent parts of our collective identity and sense of community. In divided societies, though, these narratives can be more hotly contested.

But consider this: If you are from the United States, can you imagine Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the spiritual home of the American Republic, being sold off –then allowed to become derelict and decay in front of the eyes of American citizens? Well this is precisely what has happened in Northern Ireland. The Assembly Rooms in the centre of Belfast is arguably the region’s most historically important building and was once the hub for commercial life and political activism at the end of the 18th Century. Today it lies empty, decaying and at risk of collapse.

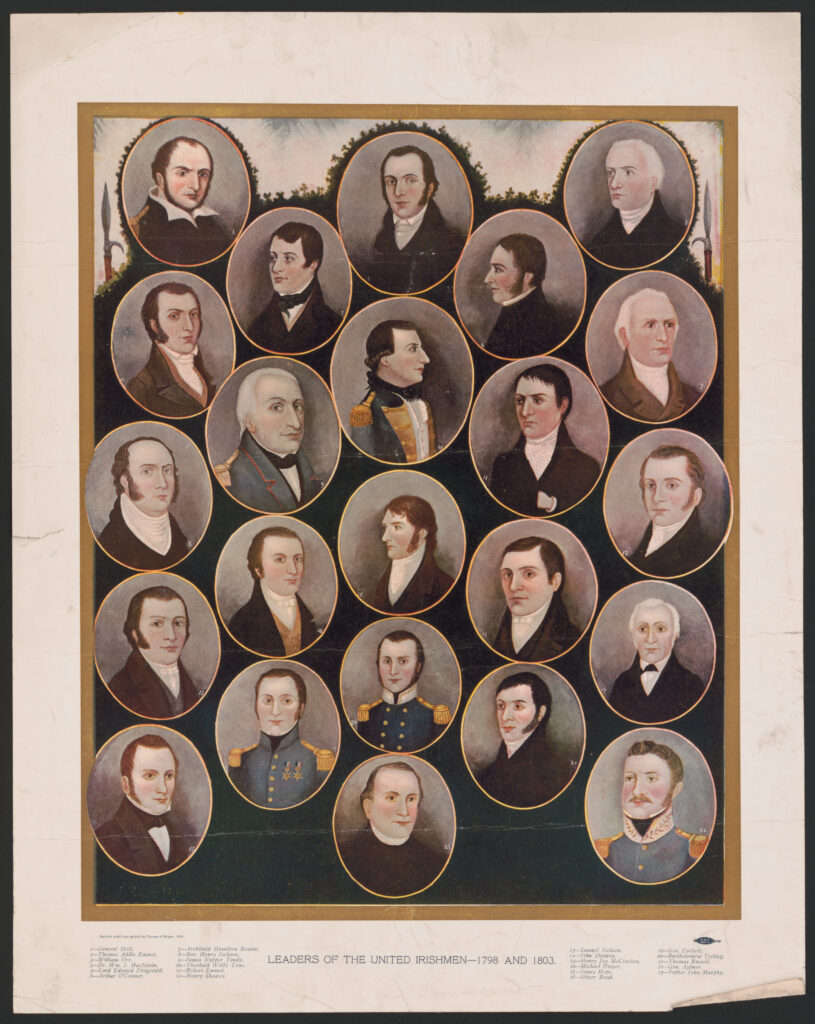

The Assembly Rooms can claim to be the birthplace of liberal democracy and Irish independence, when Presbyterian radicals, inspired by the European Enlightenment, the French and American Revolutions, and figures such as Thomas Paine and Benjamin Franklin, campaigned for Irish independence from Britain. The building became the crucible for the emergence of the Society of United Irishmen, armed insurrection and political change in Ireland.

In Belfast, the United Irishmen were mostly Presbyterians, and they embraced the pursuit of democratic change, including the cause of Catholic Emancipation. When their efforts to advance representative liberal democracy were thwarted by the British government, some resorted to violent insurrection against the Crown. While the 1798 Rebellion that resulted was a total military failure, the United Irishmen sowed the seed for physical force resistance against British Rule in Ireland, an idea that has been invoked by numerous groups since, notably the Provisional IRA during the Troubles era. This also marks a point where Irish nationalism went in two different directions, some drawing back from physical violence in pursuit of political objectives, others seeing “armed struggle” as the cutting edge of constitutional change. This remained a consistent dichotomy within Irish nationalism in the generations that followed.

The Assembly Rooms is the closest building we have left in Belfast to the birthplace of that movement. So how could it be that Northern Ireland’s most historically important building has been allowed to go to rack and ruin?

One of the reasons is because it did not fit the dominant narrative once Northern Ireland was created in 1921. Its rise and fall is emblematic of the fact that political division in the region predates the violent conflict popularly referred to as the Troubles between 1968-98. That fissure sits inside the fabric of the Assembly Rooms, Belfast City Hall and other civic buildings in Northern Ireland and provides a continuity that predates the Troubles era.

The violent conflict from 1968-98 is often regarded as a blip in Northern Ireland’s political history, a period of fracture, where those involved were just mad, bad, or dangerous to know. However, the Troubles era was not an atypical discontinuity. On the contrary, it represents the durability of political economic and cultural divisions that have been woven into the political architecture of Northern Ireland since its creation in 1921, and for several centuries before that.

This can be seen in the shape of the education system, in the nature of housing and employment patterns, sporting and cultural pursuits, political activism and voting behaviour–and in the bricks and mortar of public buildings. So in Northern Ireland the civic architecture goes beyond an aesthetic presence, with some buildings possessing a cultural, political and historical significance that connects into our existential identity.

When the British partitioned Ireland in 1921 and Northern Ireland was created, the intention was to provide stability by ensuring a clear Protestant unionist majority and a Catholic, nationalist minority. As a consequence, the unionists won every election from 1921 to 1969, and the nationalists lost. Unionists felt they had the right to political power and to demonstrate their British identity, while nationalists felt they had the right to reject the gerrymandered political system that was created.

After 1921, unionists set out to construct a region that looked and felt British, the buildings and statues reflections of an identity that they felt was under threat from the independent Irish Free State and an unreliable government in London. So the buildings themselves became emblems of identity and division, obvious to everyone who lived there. Who was allowed inside them and who was not, what statues and flags were erected in their grounds, all reflected the wider political and cultural fractures beyond their walls.

So Northern Ireland was deliberately branded as being British not Irish, and laws were brought in to reinforce that effort, including the Special Powers Act in 1922 and subsequently the Flags and Emblems Act in 1954. This legislation helped unionist governments exert political and cultural control and equate Irish nationalist cultural symbols with disorder and disloyalty. As Northern Ireland was spray-painted red white and blue by political unionism from 1921, remembering its own history of radical Protestant Irish separatism was airbrushed out of the public consciousness.

That is the context for understanding why the Assembly Rooms are lying derelict and rotting today. The story of Protestant liberal Irish separatism was the “wrong” story, one of Protestant not Catholic separatism, religious tolerance and progressiveness, rather than dogmatic spiritual prejudice, a story of European ideals and cosmopolitanism, rather than an inward-facing Gaelic provincialism. The narrative of Protestant radicalism that pioneered democratic ideas and supported the political separation of Ireland from Britain was not the story that unionist civic leaders wanted to celebrate after 1921–so they didn’t.

However, Northern Ireland has changed hugely over the last three decades and, as the peace process has developed, the civic architecture has evolved also. During the height of the Troubles era in the 1970s, the region was architecturally warped out of shape. The urban landscape became like no other place in the United Kingdom or Ireland.

Crossing the Irish border involved long queues under the gaze of fortified army watchtowers, with the British army on one side and the Irish on the other. There was no doubt that you were moving from one country to another or that the Northern side of the border was a site of strife, tension and violence. The civic architecture during those decades was a visceral and shrill statement of imminent threat and emergency, evident in the urban infrastructure.

Court houses and police stations were surrounded by barbed wire, sandbags and wire mesh. The centre of Belfast was enclosed in steel security gates and body searches by the police and army became a daily experience for everyone.

This militarised civic architecture had an impact on the people who lived there just as much as any laws that were passed or elections that took place. It shaped behaviour, as having to go through wire mesh security gates with video cameras on the door, just to go into a bar, or navigate your way around the ironically named “peace walls” that proliferated in Belfast during the Troubles era, made it clear that you lived in a conflicted and divided society. The peace walls began as temporary ad hoc fences erected by the British army in 1969 to keep nationalists and unionists from attacking one another in flashpoint areas of Belfast and Derry, but they quickly became permanent fixtures and multiplied like a rash in urban areas.

Despite this architectural doomscape, the civic space in Northern Ireland has evolved in line with the peace process since the 1990s. The watchtowers have vanished, along with the sandbags, army check points and wire mesh. However, the ‘peace walls’ in so-called ‘interface’ areas of Belfast and Derry, where Catholics and Protestants live in close proximity, have been slower to disappear.

While the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, it took another 18 years before the first wall was dismantled in 2016 (there are still nearly 100 barriers of various types left). While there was a policy goal within the governing Northern Ireland Executive to remove all of the remaining walls in the city by 2023, this aim is hopelessly behind schedule. This relates to the fact that the inherent structural divisions within the society have not dissipated and there is a fear at the community level that if the walls come down–sectarian violence will erupt on the streets.

“Peace Gates” have been introduced in some places as a halfway house, opened for people to move around during the day but closed at night when tensions are higher. These peace walls are now a tourist attraction in their own right and the numerous political tours in Northern Ireland bring visitors to view our concrete steel and wire dividing line that remains, like a scar on our belly after the major surgery of the peace process. Our scar isn’t as red as it was–but it’s certainly still a visible reminder of our recent illness.

Despite the walls that remain, the civic architecture of Northern Ireland has changed utterly in recent decades. The key reason for this is that the region has undergone a revolution in its political demography since the Troubles era. There is now greater cultural diversity and a balance between Catholic/nationalist and Protestant/unionist voters, while the civic space is changing to reflect that new reality.

There is now greater political and cultural space to rediscover the Assembly Rooms as a key part of the region’s heritage and there is a vigorous campaign ongoing to save the building from its current owners, an international property development company who have failed utterly to maintain it. Other civic buildings and public spaces are also being reimagined to reflect the shared society that many aspire to have.

A life size bronze statue of US anti-slavery campaigner Frederick Douglass was unveiled in Belfast in 2023. Douglass, who was born into slavery in Maryland in the early 19th Century, toured Ireland during the 1840s. Belfast became the first European city to erect a public statue in his memory, again demonstrating the increased cultural diversity that is beginning to creep into Northern Ireland’s civic architecture.

Feminist revolutionaries such as Mary Ann McCracken and Winifred Carney are being rediscovered and given representation in civic spaces. Life size bronze statues of McCracken (a Presbyterian, and militant Irish republican) and Carney (a Sinn Fein and trade union activist, and member of James Connolly’s Citizen Army who participated in the 1916 Easter Rising) were unveiled in the grounds of Belfast City Hall in 2024. These two now stand within spitting distance of the massive statue of Queen Victoria, reflecting the more balanced political complexion of Northern Ireland today and the commitment to a shared civic space.

While at street level there is still a visible demarcation of areas in binary terms as being British or Irish, with flags flown on lampposts and kerbstones painted red white and blue, or green white and orange, there are also signs of change here too.

Wall murals are now more diverse than they were in the Troubles era, and while paramilitary related murals remain, their tone has diversified to include a wider range of themes. A new wave of street murals showcasing the trade union movement, and highlighting women and the LGBTQ+ community has emerged, alongside artwork featuring the Titanic, and in Derry, a much-visited mural of the Derry Girls from the hit TV show. The “International Wall” on Belfast’s Falls Road meanwhile, features scenes from a number of human rights struggles and connects local political themes with conflicts beyond Northern Ireland. In 2024 large sections of the wall were given over to murals in support of Palestine and opposing Israel’s bombardment of Palestinians in Gaza.

Despite these recent advances, political and cultural divisions remain buried within the structural DNA of Northern Ireland’s civic architecture. The fate of the Assembly Rooms is emblematic of how our urban space can shape public narratives of political and cultural legitimacy. A powerful history endures in Northern Ireland’s civic buildings that is only starting to emerge, of romantic ideals, inspirational leaders, and political activism. The story of the United Irishmen, who took Thomas Paine’s and Benjamin Franklin’s ideas and built them into a liberal democratic revolution, is still largely hidden in the bricks and mortar of buildings like the Assembly Rooms.

So there is something in the walls in Northern Ireland. They are bonded together by a history of division and conflicting identities, our unique conflict archaeology gradually being revealed as our peace process moves slowly forwards.

The walls can talk – if you give them the chance.