STEM, Policy, and Representation

The Trump administration has ushered in a new era for U.S. technology policy. Executive Order 14151 calls for the dismantling of DEI initiatives across the federal government. This decision threatens efforts to build a more inclusive Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) workforce, potentially limiting opportunities for underrepresented communities in these fields.

All of this shifts priorities for programs launched under the CHIPS and Science Act. Before Executive Order 14151, much attention focused on funding levels and allocation processes. The Regional Technology Hubs program, managed by the Economic Development Administration (EDA), was intended to strengthen America’s scientific and technological ecosystem while addressing workforce needs in the growing tech industry. Under the Biden administration, EDA made equity and inclusion a priority, even as researchers have noted issues with this stated objective as it lacked a clear “inclusive innovation strategy.” Despite this gap, the program offered a key opportunity to advance equity in the STEM ecosystem.

The STEM workforce has become more diverse over the past decade, but significant racial disparities persist. According to a 2023 report from the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, white workers still make up the largest racial and ethnic group in the STEM workforce (at 64%). Hispanic workers followed, with 15%, Asian workers with 10%, Black workers with 9%, and American Indian or Alaska Native workers less than 1%.

Underrepresented minorities–including Hispanics, Blacks, American Indians, and Alaska Natives–comprised nearly 24% of the STEM workforce in 2021, marking an increase from 18% in 2011.

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and other Minority Serving Institutions have been uniquely positioned to support this mission. For instance, HBCUs play a pivotal role in producing Black graduates in STEM fields and have established important partnerships with organizations like the HBCU-IBM Quantum Center and Google AI Institute.

Despite their track record of innovation, only a small number of HBCUs received funding through the regional technology hub designations, even though approximately eight were included as partners. While these issues—including the Trump administration’s policies–pose immense challenges, this shift also presents an opportunity for new leadership outside of government—from industry, academia, and philanthropy to step in and drive inclusive innovation forward.

The Science and Chips Act

A 2021 report from the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics shows how workers in STEM fields drive a nation’s capacity for innovation through their involvement in research and development (R&D) and other technologically advanced endeavors. For example, the healthcare market for 3D printing saw a significant increase during the COVID-19 pandemic, becoming a vital source for hospitals to acquire personal protective equipment and medical devices. Furthermore, in 2023, 83% of U.S. consumers used a subscription video-on-demand service, a rise of more than ten percentage points in five years.

Yet, according to a 2022 National Science Foundation report, the United States is falling behind in STEM fields. China has passed the U.S. in critical areas, including the number of natural-science Ph.D. graduates and the publication of scientific and engineering research papers.

This trend is echoed in a recent study by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) and Oxford Economics. Findings reveal the U.S. semiconductor industry workforce is projected to grow by nearly 115,000 jobs by 2030–from approximately 345,000 jobs today to about 460,000 jobs by the end of the decade. This means that, without a comprehensive strategy to address workforce shortages and skills gaps, about 67,000 jobs for technicians, computer scientists, and engineers in the semiconductor industry risk going unfilled by 2030. While evidence to support a shortage of STEM workers varies based upon the field type, the Chips and Science act has been recognized as a valuable tool for incentivizing STEM education and training to help address workforce shortages in critical technology fields.

Barriers to Innovation for HBCUs

HBCUs have proven to be powerful agents of change, effectively tackling racial disparities within science and technology fields across various STEM disciplines. HBCUs are institutions of higher education founded with the primary goal of educating African American students and other minorities. Because of segregation laws and widespread racial discrimination, African Americans were largely denied admission to traditionally white institutions at the time. HBCUs first appeared in 1837, with Cheyney University of Pennsylvania, which was quickly followed by a slew of others, particularly after the Civil War and during the Reconstruction period. The Higher Education Act of 1965, as amended, officially defined an HBCU as any historically black college or university founded prior to 1964, whose primary mission was and continues to be the education of black Americans.

HBCUs operate in a distinctive economic landscape that is shaped by several factors affecting the growth of their R&D enterprise. According to a 2021 brief from the National Science Foundation, HBCUs have experienced growth in Federal Science & Engineering support in Science and Engineering, but there is still an overall long-term decline since the early 2000s.

This disparity reflects broader challenges HBCUs face in competitive grant processes. For instance, many HBCUs are underrepresented among Research-1 (R1) institutions in the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. Currently, only 11 HBCUs hold R2 status, which indicates high research activity and qualifies them for competitive research grants and contracts. Beyond these institutions, at least three HBCUs hold R3 status, categorizing them as Doctoral/Professional Universities with limited research activity.

The majority of HBCUs remain primarily teaching-focused institutions, emphasizing undergraduate education with fewer graduate research programs. Consequently, only a small subset of HBCUs possesses the capacity to meet conventional research standards, limiting their ability to compete for major research funding.

This national trend, also present at the state level, led the Biden administration to call for governors across the U.S to fund land grant HBCUs more equitably. Furthermore Adam Harris, author of The State Must Provide: The Definitive History of Racial Inequality in American Higher Education (2021) has shown how a history of underfunding that has limited HBCUs’ ability to expand and modernize facilities, attract top faculty, and offer competitive programs. As Harris argues,

Higher education is organized so the institutions with the fewest minority students have the most money, the best services for students, and the highest prestige—not merely private colleges, but public ones as well. That is not by coincidence, but by design. From its inception, the state higher-education system we recognize today was built not on equality, or even an ethos of broad accessibility, but on training a white workforce. Black students were excluded.

HBCUs: Building Capacity for Innovation

Today, HBCUs provide a culturally rich environment and serve students of all races, though they continue to serve African American students disproportionately. HBCUs make up only 3% of all four-year nonprofit institutions. Yet they enroll 10% of all Black students and award 15% of bachelor’s degrees. Moreover, HBCUs contribute significantly to STEM education, granting 25% of STEM bachelor’s degrees earned by Black Americans. Despite often being under-resourced in comparison to other institutions, HBCUs have had a significant impact on the American educational landscape, producing distinguished alumni who have become leaders in politics, business, science, and the arts.

While there is often a mischaracterization of HBCUs at the state level, these institutions generate about 14.8 billion in economic impact annually. Furthermore, HBCUs have been instrumental in the creation of an African-American middle-class. According to a 2019 research report from the Rutgers Samuel Dewitt Proctor Institute, HBCUs educate far more low-income students than predominantly white institutions, and more students experience upward mobility at historically Black rather than predominantly white institutions.

This progress has broader implications for reducing economic inequalities and improving community financial security.

Even with these challenges, HBCUs continue to excel across the STEM ecosystem. For instance, a 2023 study conducted by the Brown University Annenberg Institute highlights HBCUs’ contributions to creating unparalleled learning environments that promote excellence in STEM education and pave the way for better long-term outcomes for students.

Additionally, a 2023 report from the Sloan Foundation found that 31% of Black students who attained STEM PhDs in the United States between 2010 and 2020 earned their bachelor’s degree from an HBCU. Moreover, this report reveals that 11 HBCUs rank among the top 20 institutions for awarding bachelor’s degrees to Black and Hispanic STEM PhD recipients. This underscores the pivotal role HBCUs play in fostering academic excellence and diversity in STEM fields.

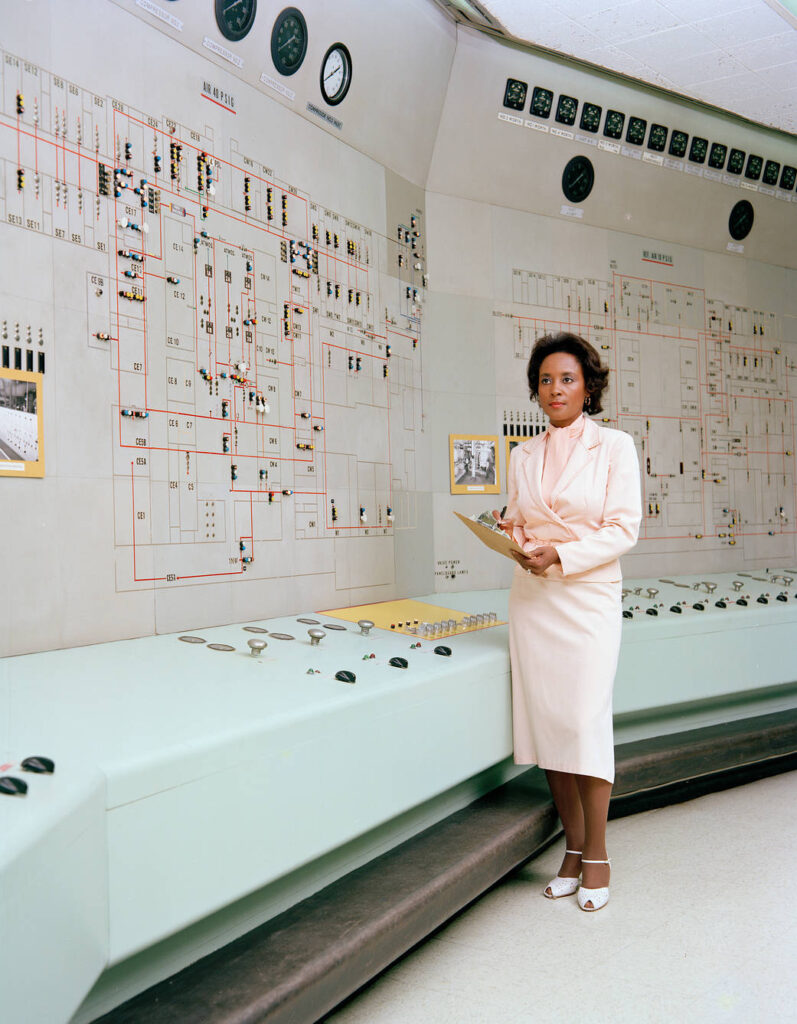

Margot Lee Shetterly’s Hidden Figures recounts the achievements of three female African American mathematicians–Katherine Goble Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson–who received their training at HBCUs and worked at NASA during the Space Race. Hidden Figures celebrates the professional achievements of these trailblazers and underscores the importance of diversity and inclusion in STEM fields, highlighting the role of HBCUs in nurturing talent and fostering opportunities for underrepresented groups.

The CHIPS and Science Act created a significant opportunity to expand inclusive workforce development and research in STEM, aligning innovation with industry and societal needs. However, policy shifts under the Trump administration have altered the landscape, requiring a new approach to ensure that underrepresented institutions, particularly HBCUs, remain key players in the technology and innovation ecosystem.

Despite uncertainty surrounding funding and the inclusive goals of the regional technology hubs program, HBCUs must continue to showcase their expertise in driving technological innovation. Their long-standing strengths in STEM education, workforce development, and community engagement position them as valuable partners in advancing national goals.

While the political environment has shifted, the need for a diverse and well-trained STEM workforce remains critical. HBCUs play a vital role in bridging the representation gap in tech, ensuring that innovation reflects the full breadth of American talent.